Book-learning, while useful, can only get you so far on the path toward competence. This is especially true in the arts. To learn a thing, often you simply have to do a thing.

Book-learning, while useful, can only get you so far on the path toward competence. This is especially true in the arts. To learn a thing, often you simply have to do a thing.

But some learning curves are steeper than others. Some roads to knowledge are pitted with potholes. And along these paths there are always tigers in the bush, lying in wait, ready to ambush the unaware, the over-confident, the ignorant.

As recently mentioned, I am learning how to weave fabric using a rigid heddle loom, turning yarn into cloth. I began by reading books on the topic—primers and how-to manuals mostly—as well as by watching instructional videos. These were invaluable, giving me a sound enough foundation in the what/how/why of the craft, that I felt confident to purchase a loom and try my hand at the techniques I’d been reading about and viewing.

But, in any journey of knowledge, there are some elements that are so basic as to be considered already known. Axioms, truths, assumptions, things everyone knows; except, they’re not things everyone knows. Rather, they are things so basic that, if you know them, you forget that not everyone knows them.

Things like, how to open a hank of yarn.

We all know what a ball of yarn is. It’s not a hard concept to grasp. It’s a ball. Of yarn. You know, the thing cats play with. One of the ends is on the outside and the other is hidden, tucked away at the center of the ball. In the picture, it’s the small grey thing at lower right.

If you wind a ball of yarn but leave the center hollow, you get a cake of yarn. Cakes have one end on the outside, but give you access to the one at the center, too. You can pull from one, the other, or both. There are three of them in the picture.

You also might know what a skein of yarn is. It looks like a big ball of yarn that’s been sort of (technical term) smooshed into a football shape. As expected, it has one yarn end on the outside, but it also (often) has one that comes out from the center, and either one can be used.

Ball, cake, skein, these can be used as is, without issues.

But a hank of yarn? What the hell’s a hank?

Up until this week, I had no clue what a hank was, much less how to handle one. And none of my reading or weaving tutorials mentioned the term. Neither did any of the myriad tip-sheets on yarn have anything to warn me about what I was getting into.

So, when the box of yarn I’d ordered showed up this week—lovely yarn made of merino and cashmere, yarn so soft and light that I can barely feel it with my callused old-man fingers—I opened it up and, rather than the balls, cakes, or skeins I’d expected, I found only twisted, corkscrew spirals of yarn. Hanks. I’d seen them, but never held one before and, as I turned it over in my hands, it was clear that they had no discernible end, no visible access point.

I quickly figured that I was in trouble.

And I was correct. In the picture, the mare’s nest to the left is the trouble I found. It represents the first hank I opened.

It’s a ruin.

If I’ve learned one thing in life, it’s that mistakes are teachers. Mistakes can flatten learning curves. Mistakes can fill in the potholes waiting along that road of knowledge. Mistakes can alert you to the tigers.

But you have to let the mistakes do their work. You have to learn from them.

I have several more hanks to uncoil and wind into usable cakes. I am filled with trepidation as I proceed because I’ve proven that I can ruin the yarn; however, I’ve also proven that I can successfully cake-up said yarn, if I pay sufficient attention.

Fingers crossed.

k

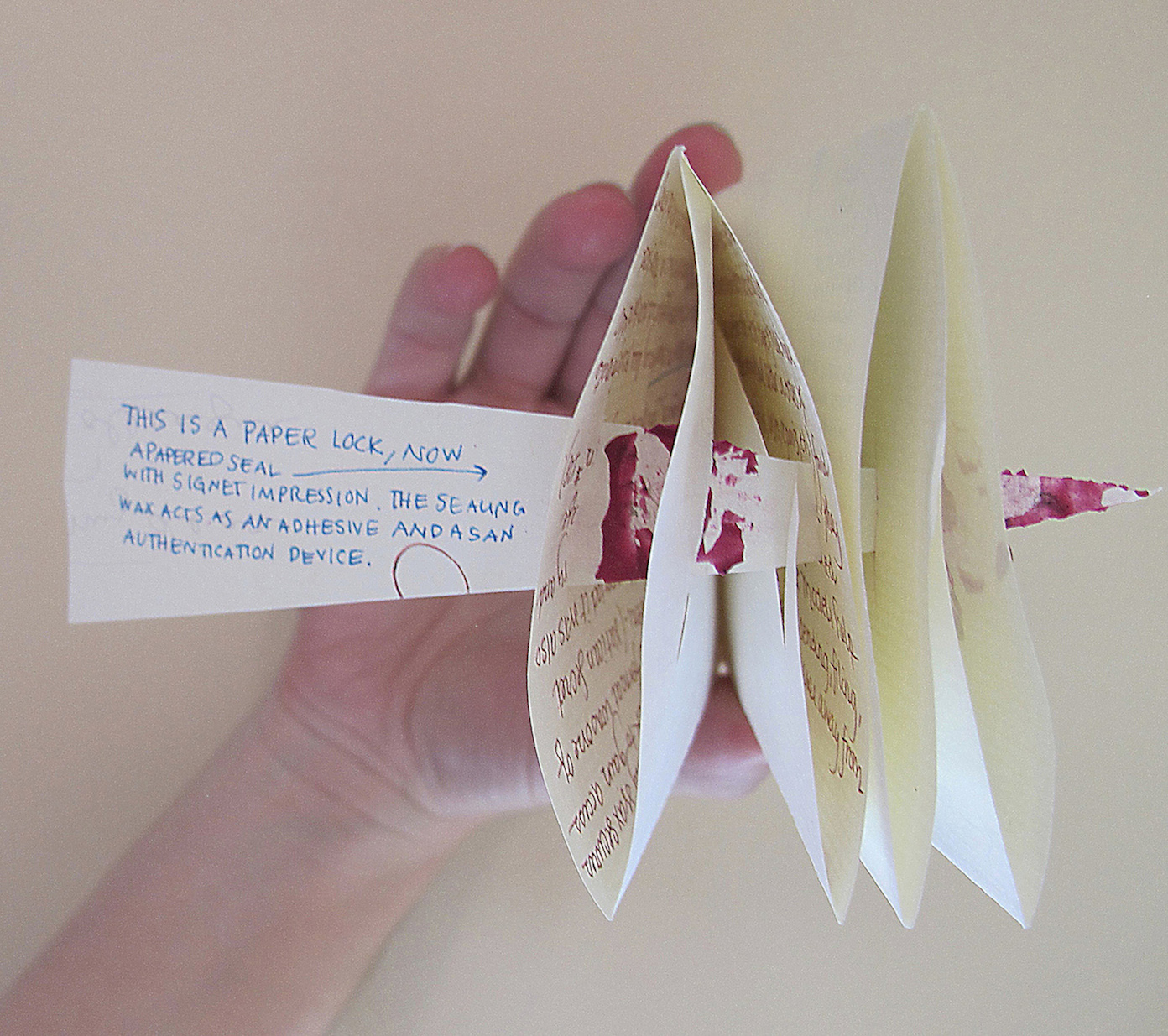

A while back, I performed a small experiment with old letter writing techniques. As a result, I learned a great deal about

A while back, I performed a small experiment with old letter writing techniques. As a result, I learned a great deal about

Unraveling Time

Unraveling Time Desert Wind

Desert Wind Ploughman's Son

Ploughman's Son Ploughman King

Ploughman King The Year the Cloud Fell

The Year the Cloud Fell The Spirit of Thunder

The Spirit of Thunder Shadow of the Storm

Shadow of the Storm The Cry of the Wind

The Cry of the Wind Beneath a Wounded Sky

Beneath a Wounded Sky Cryptogenesis: A Memoir

Cryptogenesis: A Memoir