As regular visitors are aware, I have a strong perfectionist streak. My sister and I both struggle with it, but I couldn’t tell you if it is nature or nurture that infected us with this scourge. (As with most things, probably a mixture.) Neither of us would ever say that we are perfect, or even that we were close. Perfection, as I’ve often said, is unattainable, but that does not make my inner compulsion to achieve it simply disappear. It does, however, drive me batty.

But I may have found a cure. At least one that shows promise.

When I think about perfectionism, I have to recognize that it is all about control. Control (whether it be of input or environment or technique) and outcomes. And those outcome must be measurable, so they might be compared to the ideal and thereby be found wanting. Naturally, some things lend themselves more readily to this kind of rigor. Maths and engineering, for example, are much easier to control and evaluate. Skills, too, are easier to measure; whether you’re building a cabinet or shooting an arrow, it is clear to see whether the corners are square or the bullseye was hit. When you wander into the more artistic realms, though . . . that’s when it gets sticky. What is a perfect performance of a Bach partita? What is a perfect novel? What is the perfect lasagna recipe?

Trying to achieve perfection in an artistic endeavor is—let me be blunt, here—just plain stupid. And yet, it’s what I’ve tried to do for sixty-odd years. I cannot shake it. I cannot not try to do it perfectly. That partita, that novel, that recipe, I’ve tried, over and over again, to do all of them, without error, without flaw, but each time, be it my fingers, my prose, or my mastery of timing and materials, I have failed and every result has been, well, imperfect. There’s always something, whether I stumble on the high notes, or my books sell like shite*, or there’s a burnt bit on the corner of the dish.

But there’s one thing that all these activities have in common: they don’t fight back. That perfect iteration, that flawless performance, it is out there in the Platonic ether, taunting me, and the only thing keeping me from it is . . . me. My skill. My technique. My concept.

Quite recently, however, I have discovered something of a different nature. An artistic endeavor, to be sure, and something I’ve contemplated (and been warned away from) for a long time, since boyhood, to be honest. It is a creative outlet that is unpredictable, nearly impossible to control, capricious, fickle, and headstrong. Outcomes can be damaged due to environmental variables. Errors quickly become irreparable. And speed in creation is absolutely essential. In short, all the makings of an artistic disaster.

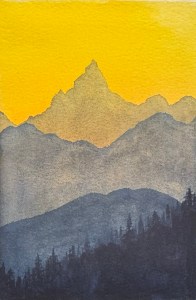

Allow me to present: watercolors.

Yeah. Watercolors. Like those collections of pre-fab paints we had as kids (because they were easier to wash out of our clothes). Those watercolors.

My father was an artist. Some of my earliest memories are of him in his studio, perched on his high wrought-iron chair, the air hazy with the scents of linseed, turpentine, and pipe tobacco. He was a graphic artist by trade, a lithographer by profession, but at home he sketched in pencil and charcoal, and painted in oils. His workplace was a controlled chaos of books on anatomy and art, of canvases stretched and rolled, the whole dominated by a large ink-stained drafting table near the door and an easel further into the room. I remember watching him working on a particular painting, scooping up gobs of titanium white with his palette knife to create an impasto sun over a southwestern desert, saying how much he liked painting in oils because “I can always scrape it off and start over. Not like watercolors. Watercolors do not forgive.”

And they don’t.

My journey in watercolor painting is only a couple of months old, but already I have learned, first-hand, exactly what my father meant. For as long as I work toward mastery of watercolors, for as long as I attempt to control the medium, they will fight me, with every step, every brushstroke. I will never learn how to succeed as a watercolorist. I will only learn how to fail less often.

And that, my friends, is my cure for perfectionism.

Find something that cannot be mastered, something that cannot be controlled but only cajoled, entreated, encouraged to give you what you want. And I don’t mean only watercolors; it could be anything, from raising orchids to fly fishing to coaching Little League. By falling in love with something that will not be controlled, in order to improve, I am the thing that must change, not only by learning to adapt to the quirks and whims of the thing, but by accepting the thing with its quirks and whims, and yes, even because of them.

I will never be a master watercolorist, but having spent just a few brief weeks playing with the medium, learning about it, seeing what it can (and cannot) do, I know that I do not want to be a master watercolorist. I do want to know more, do more, acquire more skill so that I can at least approximate on paper the pictures that I envision, but I know I will struggle to achieve even those modest goals.

Which, to be clear, is my intention. I want to be imperfect, and to be happy with that imperfection. To strive. Not to master. To accept. Not to control.

I only have so many summers left here, and I do not care to waste them dancing to the perfectionist’s tune.

k

*Just a grateful shout-out here, to those who have read my books, including the two people who recently ripped through the Fallen Cloud Saga (Yes, my sales are that low). Thank you, and I hope you enjoyed the books enough to recommend them to others.

Last week’s post

Last week’s post