AI; the grift that keeps on grifting. Feed it, press a button, and (in the immortal words of our president) “Bing Bong Bing,” there you have it: AI slop.

AI; the grift that keeps on grifting. Feed it, press a button, and (in the immortal words of our president) “Bing Bong Bing,” there you have it: AI slop.

It’s everywhere, now including your bookshelf. If you’re not careful, that is.

And we weren’t.

We wanted to read Robert Reich’s new memoir, Coming Up Short, so we went to the Evil Empire (aka Amazon) and searched. “What format?” was the question. Hardcover, Paperback, Kindle, or Audio? Paperbacks are easier on our ancient hands, so that’s what we picked. And there was our first error. I did not see the red flag, did not twig that this was a new release, available in both Hardcover and Paperback? That never happens. If you get a hardback deal, publishers aren’t going to undercut that with a simultaneous paperback release. Sadly, all we saw was the reduction from the hardcover price (expected in a paperback), so we dropped that turd into our cart and hit the checkout.

My bad on that score.

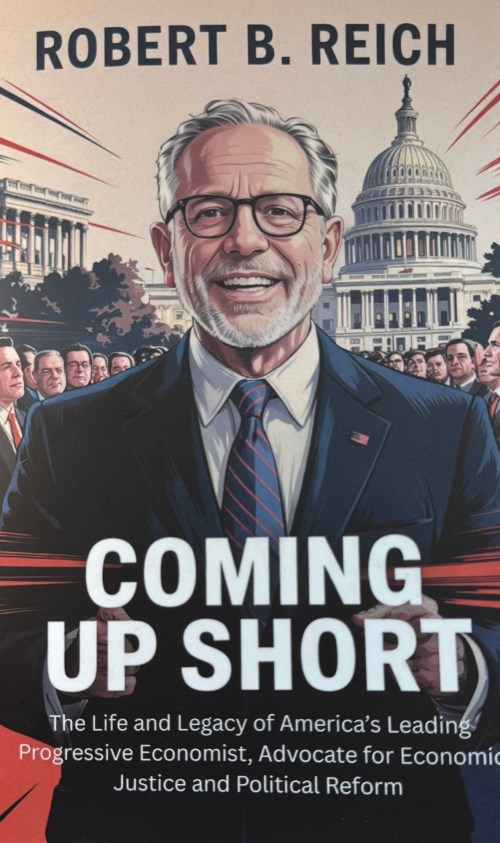

When the book arrived, it was (as my wife described it) like opening a door to an alternate universe. I was coming up the stairs as she first viewed our purchase, and all I heard her say was, “….the hell?” The cover (pictured, right) was unlike anything we’d ever seen on a new release from a major publisher. It was also about half the thickness of a major release (150 pp vs the 400 pp of the hardback).

….the hell? Indeed.

What we had purchased was a bunch of AI slop.

Someone—definitely not Shem Grant, the named author of this tripe, whose magnum opus has now been de-listed from Amazon—fed a bunch of open source info into an AI chatbot, had it spit out enough slop to fill the 150 pages required to give it a spine, slapped a cartoonish rendition of its subject on the cover, and voila, instant grift. I’ll admit, I’ve not read this “product,” but in skimming through I found it repetitive, composed much like a high schooler’s book report, and rife with errors (within three minutes I fact-checked two: Reich was born in Scranton, not New York, and he was a Rhodes Scholar, not a Marshall Scholar).

Yup . . . AI slop.

Is this a thing? I wondered. Heading back out to Amazon, I executed similar searches for new memoirs and found similar AI-generated knock-off versions:

- Jacinda Ardern’s A Different Kind of Power had half a dozen slop versions

- Liz Cheney’s Oath and Honor had a few grift versions, plus about a dozen “workbook” editions

- Kamala Harris’ 107 Days had fifteen (!) “books” that included the phrase “107 days” in their title, all by “authors” who had no other titles to their credit

In addition to these obvious attempts to con buyers by piggybacking similarly titled slop onto the sales of new releases, there were many self-styled “biographies” that had dubious authors, were listed as “independently published,” and often had obviously AI-generated covers (some that were really bad, and I mean like embarrassingly bad).

So, this stuff is out there, and there is a lot of it.

Remember when self-publishing became a thing? Remember how everyone wrung their hands over that? “There’s already enough crap out there in the book-sphere, and now everyone who can hold a pencil is going to think that they’re a writer!”

Hehe. Good times, eh? Because now, not only can anyone with enough grip strength to hold a pencil pose as a writer, but all those who are too lazy to even pick up a damned pencil are able to churn out utter rubbish, slap a fake name and an SEO-optimized title on it, send it into the Amazonian jungle to sting the unwary, reap the grift, and move on.

It’s enough to make one want to give up.

But, lesson learned. Once burned . . . .

k