For about three months there has been one main question on my mind: What grade of cancer is it?

For about three months there has been one main question on my mind: What grade of cancer is it?

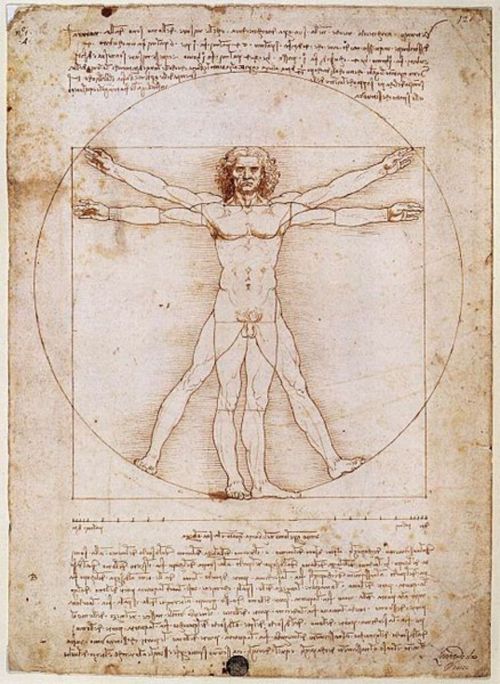

For the past 65+ years, my body has been pretty reliable. Aside from bad eyes, soft teeth, and legs too short for my height, it has performed well. Oh, there have been episodes—a back injury that plagued me for decades, a stress level that led to a barrage of investigative tests, a critical bout of appendicitis—but I’ve reached retirement age without needing any prescriptions and my main complaints center around stiff joints and thinning hair.

In short, my body has been a real trouper.

I’ve also tried to approach life with a “data-driven” mindset, where study and expertise gather and analyze information in order to formulate probable outcomes and guide my actions. Just as I trust that someone who has studied turtles for thirty years knows more about turtles than I do, and that someone who restores cars knows more about internal combustion than do I, so too do I trust that medical professionals, who have years (sometimes decades) of study and experience under their belt, who are steeped in the knowledge and research of their chosen field, are better qualified to interpret the results of medical tests than I am.

So, in January, when blood tests came back that showed an elevated PSA level, and my doc was concerned that this indicated a 25% chance that I had developed prostate cancer, I was likewise concerned. A 25% chance wasn’t big, but it wasn’t nothing, and we agreed that further investigation was warranted.

Then, in February, when the MRI she ordered showed a lesion on my prostate, and that lesion was determined to have an 80% likelihood of being cancer, my data-driven mindset accepted a cancer diagnosis as the most likely outcome, and the only thing left to determine was what “grade” of cancer it was. Was it the “low” grade type—not aggressive, slow-growing, low risk of complication/metastasis—where the consensus recommended monitoring rather than any active measures? Was it the “intermediate” type, where risks increased, treatments became more active, and outcomes a bit more squishy in predictability? Or the “high” grade, where invasive, sometimes radical treatment was indicated?

Looking deeper into these grades, I learned that about half of such cancers were in the “low” group, and 40–45% were in the “intermediate” group. That left only 5–10% of cancers in the “high” group. To know what grade of cancer, though, required a biopsy and because of the lesion’s location, not an easy biopsy. I will not go into details.

And it was in that month, waiting to have the biopsy, and then the near fortnight between biopsy and results, that my data-driven mindset failed me.

Cancer is not a fun word. It does not wrap one up in a warm blanket of fuzzy good feelings. Having friends and relatives who have battled and (thankfully) made it through their cancer treatments, I know that cancer is not a death sentence. However, having had a mother and step-mother die of cancers, I know that this is not a given. Cancer can and does kill. Often. And though I’ve long heard that “If you get cancer, prostate cancer is the one you want to get,” that men with low-grade prostate cancer often live for decades and usually die of something else, and though I was looking at a 90–95% chance that this cancer was low or intermediate grade, none of that mattered as my data-driven mindset was overcome when my reptilian brain took charge and spent those six weeks between scheduling the biopsy and receiving the results in a fight-or-flight battle with the 5–10% probability of a “high” grade diagnosis.

And I mean a serious battle. Like, a Why bother planting those roses? battle. A No point outlining that novel now scale battle. An I worked so fucking hard to make a safe retirement for us and now this? cage-match battle.

There was no 90–95% chance. Try as I might, despite desperate attempts to focus on the real probabilities, there was only the 5–10%.

During those six weeks my fears blossomed, unfurling their cankerous petals, until Week Three when they began to wither and fade as within me there began to grow a stony, reluctant acceptance. “Worst-case scenario” began to preface much of my thinking, and I started the process of evaluating my life, cataloguing faults and failures, strengths and successes, all in neatly-ordered columns. Aside from the fact that I was really really looking forward to having another quarter-century (give or take) to doink around on the planet, if I did have to “get my affairs in order,” I felt like I’d done a pretty good job of it, overall, and those who depended on me would be taken care of.

It wasn’t a peaceful state of mind, it wasn’t pleasant, but it was acceptable.

Yesterday, the results came in. No cancer. None. Nada. Zip. Due to the difficult position of the lesion, he’d taken three times the usual number of core samples he usually took, just to make sure. All came back negative for cancer.

Remember, up top, when I mentioned that the lesion seen in the MRI had an 80% chance of being cancer? The 80% that has driven my thinking for months? Turns out I’m in the other 20%. Probabilities are just that: probabilities.

Do I regret my data-driven approach to all this? No. Concentrating on the most likely outcomes, while remaining cognizant of the outliers, was a gentler journey than driving blithely down the “happy path” only to smash into a brick wall, should my diagnosis have gone the other way.

I am grateful, exceedingly grateful, that it worked out as it did. I’m grateful for the strength and steadfastness of my wife. I’m grateful for the caring and empathetic treatment from my medical team (nurses absolutely rock). And I’m actually grateful for the opportunity I was given, to see my life from a new perspective, to evaluate my existence in the aggregate rather than the discrete, and to experience this “soft reset” that will now color and inform my approach to what I hope is another quarter-century (give or take) to doink around the planet.

Onward.

k

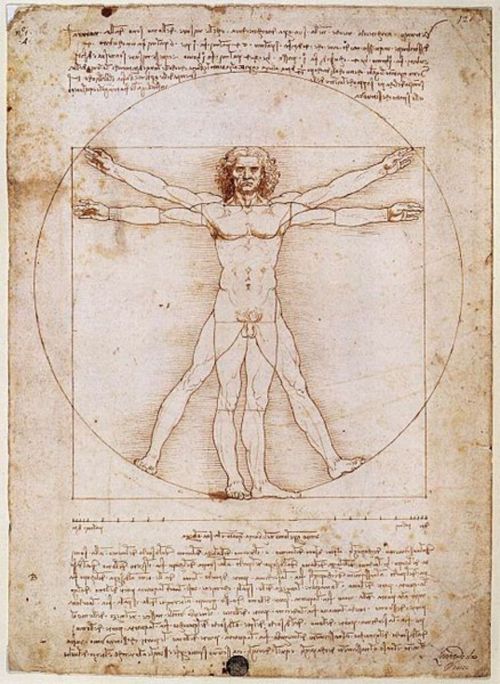

to these old eyes

to these old eyes